ROGER K. LEWIS’ LETTER TO EMERGING DESIGNERS

https://www.architectmagazine.com/design/roger-k-lewiss-letter-to-emerging-designers_o

As an honor to his career in architecture and education, we are publishing a letter he wrote to emerging designers back in 2013.

In Memoriam Roger K. Lewis (1941 – 2024)

While attending architecture school, Roger K. Lewis authored a book, Architect? A Candid Guide to the Profession (1985); it impacted my path in architecture and those of many others. Ironically, I had the pleasure and honor of serving with him in the School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at the University of Maryland many years later. Further, he was more than supportive when authoring my own career guide – Becoming an Architect: A Guide to Careers in Design (2014).

Posted on: September 13, 2013

As his updated edition of ‘Architect? A Candid Guide to the Profession’ hits shelves, critic, architect, and educator Roger K. Lewis has some pointed advice for emerging designers.

Stephen Voss

By Roger K. Lewis

Are you wondering what lies in store for you given the current state of the profession and the recent, profoundly stressful challenges faced by your generation of designers—the Great Recession, work slowdowns, unemployment, stagnant incomes? Beyond economic uncertainties, you face other significant challenges: choosing among ever more diverse career paths and roles; thinking critically about always shifting and often short-lived aesthetic trends, such as ersatz, postmodernist historicism; satisfying increasingly stringent project needs and constraints; and keeping abreast of rapidly evolving, innovative technologies.

Yet the basic mission of architecture, considered the world’s second oldest profession, has not changed. Although modern technologies, specialization, and design theories have transformed how architects are educated and practice, most practitioners still do essentially what the Greeks and Romans did: design buildings.

Nevertheless, it’s no surprise that in this uncertain age you may be angst-ridden as you ponder your future in the profession. If you are an intern, you may already feel put upon by the ordeal of accumulating thousands of hours of experience and having it validated to satisfy licensing requirements. You may even be considering deferring your path to licensure.

But do not despair. I assure you that despite any frustration or skepticism you may feel, architecture is still an extraordinarily stimulating calling, offering artistic and intellectual fulfillment unmatched by any other profession. Architects not only create visual poetry embodied in beautiful structures and urban settings, they also deal with pressing, real-world issues such as climate change, sprawl, affordable housing needs, and urban revitalization. We always serve two clients: those who hire us and those who inhabit or interact with the architecture we make, and who worry about safety, accessibility, traffic, and aesthetics. By designing architecture of lasting value for all stakeholders, we enable social, economic, and cultural progress. This will be your ultimate reward.

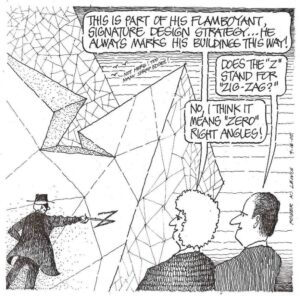

Of course, some architects seek less altruistic rewards: fame, affluence, social status, political influence, and even immortality. But these rewards are elusive and ephemeral. Responding to the public’s appetite for celebrity, the media traditionally focuses on starchitects—Frank Gehry, FAIA, Richard Meier, FAIA, Zaha Hadid, Hon. FAIA—not only because of their exceptional work, but also because they are perceived as aesthetic soloists.

But take comfort: the era of the perceived master architect is fading. Your generation comprehends that architecture is increasingly and inescapably a collaborative art. By understanding the complex process of building, you better appreciate the indispensability of other team members—owners, engineers, specialized design consultants, contractors, attorneys, investors, lenders—and even government regulators and concerned citizens.

During your first few years in the profession, out of necessity, you may work for a firm whose goals, values, and method of operation may be less than appealing or ideal. You may join a service-oriented firm that seeks to get the job done on time and within budget while maintaining profitability, or a design-oriented firm that approaches practice as an aesthetically expressive art and secondarily as a business. You may be employed by a small local office that does mostly custom homes and residential remodeling for household clients, or by a large global firm with hundreds of employees and clients in emerging markets.

Regardless of what kind of clients or projects characterize your firm, your engagement in the process of design will rapidly develop your skills and expand your knowledge. Specific project attributes—location, size, programmatic needs, budget limits, regulatory constraints—will vary greatly, yet the hands-on experience of creating real architecture for a real client and a real site, whether here or abroad, will prepare you for licensure and, when the time comes, for practice on your own.

Although the basic design process remains relatively constant, how your firm is managed nevertheless influences the type of experience you will gain. Many firms, especially small ones, are headed by a single principal responsible for the firm’s design or signature style. Larger firms are organized departmentally by function or operate as a collection of studios or discrete project teams led by partners and senior associates. They generally divide up responsibilities such as outreach and marketing, firm administration, and project design and production.

Working in a small firm, you are likely to interact with clients more frequently, help more often with marketing, and attend more project presentations and review meetings with citizens and government officials. You also may be more involved with all phases of project design, from schematics to construction administration, thereby shouldering more responsibility. Small firms typically are better at exposing interns to the breadth of practice. In a large firm, depth tends to trump breadth. You probably will work on fewer but larger, longer-term projects. You will collaborate with more specialized consultants, acquiring expertise that you might not gain in a small office. But still, each type of experience is worthwhile.

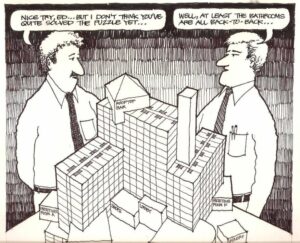

Like professors, practicing architects profess diverse, subjective design principles and theories that you may or may not embrace. Exposed to “-isms” and “-ologies” in school, designers as they start to practice are often drawn to one or more of them, including functionalism, geometric formalism, sustainability, or regionalism. Sociology, psychology, symbology, ecology, and technology can be design drivers. Some architects believe design should be guided solely by problem-solving methodology, not theorizing. As you establish your style and beliefs, beware of short-lived fads, fashions, theories, and trends.

Your generation’s concerns encompass but also extend beyond those of my generation. Chances are that you aspire to heal the planet by designing “green,” net-zero projects, whether a bus shelter, a skyscraper, or a college campus. Four decades ago, architects embraced energy conservation, but only as a reaction to a 1970s oil embargo and rising fossil fuel prices. In the 1950s and 1960s, object-fixated architects were future-oriented. Older buildings—or neighborhoods—deemed obsolete merited demolition. Today, your cohort understands that preservation and adaptive reuse of existing structures, historic or otherwise, is a key sustainability strategy and an indispensable cultural objective.

Indeed, in light of demographic shifts and the movement back into cities, coupled with the need to redevelop dysfunctional urban and suburban areas, architects are increasingly engaged in planning and urban design. They design new suburban communities or reshape city neighborhoods for which they devise new circulation and infrastructure networks, new land use and density patterns, and new public spaces and civic amenities. They also may craft urban design and architectural guidelines for buildings and streetscapes. In the 1960s, when I was a student, I never heard the word “streetscape,” much less “preservation,” “suburbia,” or “sustainability.”

With the scope of the profession growing ever more broad, you may well pursue other activities to advance the cause of architecture. You can help shape the built environment as a volunteer community activist, or by serving on boards and committees concerned with planning and design. You can assist nonprofit and civic groups to advocate growth policies or to deal with controversial projects. Through media and the Internet, you can report on development that exemplifies design excellence—or the lack thereof.

My career focused on architectural practice and education, but I also spent part of it in ways that, as a recent graduate, I would never have envisioned. Twenty-nine years ago I pitched an idea for a series of articles about architecture in the nation’s capital to a Washington Post editor. My published submissions soon turned into the Post’s “Shaping the City” column. It created new and unexpected opportunities: As a journalist as well as a professor and practitioner, I increasingly was invited to write, give talks, consult, advise, testify, serve on committees and boards, and appear regularly on radio. I gained a public voice and was able to reach a much wider audience and expand critical thinking and discourse about urban design and architecture.

Sometimes my commentary affected public policy, such as in the late 1990s, when I joined with other critics in a successful campaign to reduce the technically questionable program scope and overwhelming scale of the initial proposal for the World War II Memorial on the National Mall.

You may wield your influence by working in the public sector as an architect, urban designer, administrator, project manager, or building inspector. In government roles you can help shape land-use policies and master plans, zoning regulations, historic preservation criteria, design and development guidelines, and building codes. One of my former students at the University of Maryland, Peter May, AIA, now heads the regional office of the National Park Service and serves on the National Capital Planning Commission. Another Maryland graduate, Stephen Ayers, FAIA, is Architect of the Capitol.

Some of you eventually may forego architecture practice and public sector roles to pursue work in related fields such as landscape architecture, interior design, furniture design, graphic design, or civil engineering—disciplines for which architects have a natural affinity. You may become a construction contractor or real estate developer, or perhaps you will study business or law. If so, you will have a big advantage: architectural skills, methods, and expertise readily apply to other fields and facilitate switching careers.

In the end, though, I hope you will stick with the art and science of architecture. Despite all that’s new and different in the profession, despite the recent economic pressures, I’m confident that you will find constructive ways to advance the cause of design excellence, whether working for or acting as the client, or managing, regulating, or writing about projects. Every site, client, and project is unique, a prototype inviting imaginative design and problem-solving. This is the source of architecture’s greatest pleasures: the creation of purposeful designs embodying lasting values and principles. It may take a little time to get there, but the rewards will be well worth it.

About the Author

Roger K. Lewis

Roger K. Lewis, FAIA, is an architect and urban planner, a professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Maryland at College Park, and an author and journalist. After earning two architecture degrees at MIT and serving as a Peace Corps volunteer architect in Tunisia during the 1960s, Lewis helped start the architecture program at the University of Maryland School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, where he taught architectural design from 1968 to 2006.

A practitioner throughout his teaching career, his Washington-based architecture firm has designed or co-designed a wide range of award-winning projects. In 1998, the U.S. General Services Administration appointed Lewis to its Design Excellence National Peer Committee, which reviews the design of federal projects, and he serves periodically as a GSA design consultant. He is also a planning and architectural design consultant to other metropolitan Washington-area government agencies. His columns and cartoons have received numerous awards and have been republished nationally and internationally. In 1984, Lewis launched his architecture-themed, illustrated column, “Shaping the City,” in The Washington Post. He is the author or co-author of numerous journal articles and books, most recently the 2013 third edition of Architect? A Candid Guide to the Profession.